The Tale of the Offering

(A Lore of the Boer’s Head Tale)

Written by P.H. Boer

The Offering:

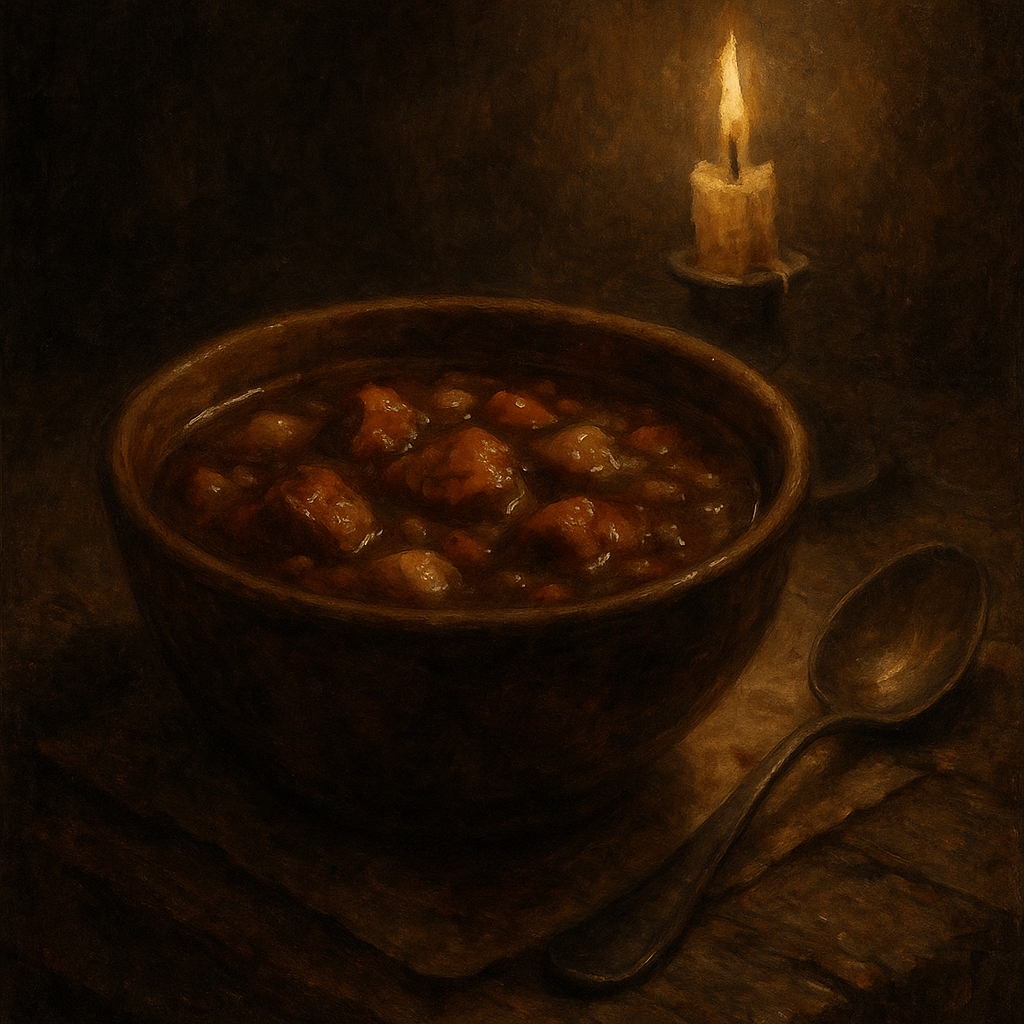

A bowl of rich, slow-cooked mystery. Served with black bread and silence. One per customer. No substitutions.

They say the stew’s recipe is older than the pub itself, older than the cobbled road that winds like a forgotten tale to its crooked door, older still than the village whose mossy bones now lie buried beneath bog and bramble.

Before the Boer’s Head had a name, before its windows learned to squint against the wind, it was just a house. A stone house. A single hearth on the edge of the world. Travelers didn’t find it so much as stumble into it. Always by accident. Always by need. Some said it walked in the fog, others that it bloomed in sorrow. But however they came to it, they arrived hollow.

And the house fed them.

The very first keeper was not yet a man then, didn’t walk like one, didn’t speak like one. Some called him a spirit of hospitality, others a boundary warden. He never gave a name, never asked for one. His eyes were deep set, like the sky had been poured into sockets and stirred.

As decades curdled into centuries, the house grew warped and weary, leaning into itself like a drunk remembering old sins. The hearth grew wider. The windows became eyes. The first innkeeper aged, slowly, or maybe learned to mimic age. He took a name. Grew a beard. Learned to chuckle and shake his head when folks called him “sir.”

He did not charge coin.

The price was always the stew and still is.

No questions were asked. The door opened. A chair creaked. The bowl arrived, unbidden and steaming. Thick and dark, swimming with root and marrow and something that defied explanation, meaty but not meat, earthy but not earth. It clung to the spoon like a second tongue.

Some tried to decline. One woman pushed it away, polite but firm. Her bowl sat untouched. When she left, she looked the same, except she cast no shadow. Not at first. Later, when she was found curled in a dry well, she cast two.

Others accepted. And afterward, they spoke in dreams. Mumbled truths to sleeping children. Drew maps to places no longer on the earth. Some wept for things they hadn’t yet lost. Some laughed until their teeth cracked. But all of them remembered.

The stew does that. It remembers.

I don’t know the recipe.

I say that without irony. Without metaphor. I truly don’t know what goes into the stew. And I have come to understand that I’m not meant to.

The pot is always full. Always warm. I never add to it. I never clean it. And yet it bubbles softly when the air grows quiet, as though stirred by unseen hands.

Patrons often ask. Some out of jest. Others, foolishly, out of genuine curiosity. They lean forward, noses wrinkling, trying to pick out ingredients.

“Is that beef?”

“Smells like rosemary.”

“I think I tasted clove.”

Let them guess. It’s safer that way.

I’ve tried to inspect it, of course. In the early days, when the pub had only just pressed itself into my mind and through my waking world, I stood over the pot with a ladle and a spoon and the kind of arrogance that only comes from not yet understanding what you’ve inherited.

I found meat, yes. But not from any animal I recognized. The muscle didn’t shear like beef or pork or fowl. It didn’t resist the blade or fall apart with time. It pulsed, slightly, before the broth claimed it again.

There were roots. But they bled when cut. And herbs that smelled faintly like letters I’d once forgotten how to read.

The stew changes slightly with each bowl. No two guests receive quite the same flavor. For some, it soothes. For others, it unsettles. One man wept after finishing it, saying it reminded him of something his grandmother used to make, though later he confessed he’d never known his grandmother. Another man claimed it tasted like a battlefield and left without finishing it. He never returned.

There are rumors, of course. Every tavern with a secret stew collects them like flies on cheesecloth.

Some say the pub itself offers up the ingredients, gathered from forgotten kitchens, dead worlds, or the memory of a meal never eaten. Others whisper that every drop ladled out is a little less of the innkeeper’s soul.

And there are older stories still. Of the stew being a form of penance. That in consuming it, the patron takes on a sin not their own. That each bowl shifts some unseen balance.

I’ve heard things whisper from the pot when the wind outside is especially cruel. I’ve seen shadows cast where there were no flames. And more than once, I’ve found names scrawled in the condensation on the wall, names of those who ordered seconds.

I don’t serve seconds.

I no longer ask what’s in it.

I don’t need to.

Because sometimes, when the pub is quiet and the fire burns low, you can hear it, soft as breath, just beneath the bubbling. The stew murmurs. Not in words, not quite. In the slosh of grief unspoken. In the names of old roads and older regrets. It speaks in memories not yet yours. It hums in warnings from futures that never made it past the door.

And if you listen too long…

Well.

Some patrons leave full.

Others leave changed.

A few never leave at all.